For the woodworker who has built items in wood with reversing grain, or super figured woods, it might seem that sandpaper is the only real option to tame the beast. It doesn’t seem to matter how long someone has been woodworking, as I’ve met both those who have been woodworking longer than I’ve been able to wipe my own nose, to those just starting out. When I start to talk about scrapers as a potential fix, I’ve received such a range of looks, from insanity, to coolness, to just complete disbelief. There are those, though, who specifically ask for scraper setup, usage, and information. Many of these woodworkers already own some form or fashion of scraper, but are frustrated with the actual results from their tool. I believe it is similar to using a well-tuned hand plane: some folks have never had the opportunity to use their scraper both sharpened and tuned so it could do more than make dust. When I bought my first personal hand plane back in the early ‘80s, I worked and worked “sharpening” it, and still the negative results relegated it to a drawer for quite some time. Point being that I didn’t have the tools to recognize just how sharp was needed, nor anything to which I could compare it. This along with the very limited sources of shared information at that time, was enough to keep me guessing and stop my progress. I hope the following information will can help some of you succeed with your scrapers.

For the woodworker who has built items in wood with reversing grain, or super figured woods, it might seem that sandpaper is the only real option to tame the beast. It doesn’t seem to matter how long someone has been woodworking, as I’ve met both those who have been woodworking longer than I’ve been able to wipe my own nose, to those just starting out. When I start to talk about scrapers as a potential fix, I’ve received such a range of looks, from insanity, to coolness, to just complete disbelief. There are those, though, who specifically ask for scraper setup, usage, and information. Many of these woodworkers already own some form or fashion of scraper, but are frustrated with the actual results from their tool. I believe it is similar to using a well-tuned hand plane: some folks have never had the opportunity to use their scraper both sharpened and tuned so it could do more than make dust. When I bought my first personal hand plane back in the early ‘80s, I worked and worked “sharpening” it, and still the negative results relegated it to a drawer for quite some time. Point being that I didn’t have the tools to recognize just how sharp was needed, nor anything to which I could compare it. This along with the very limited sources of shared information at that time, was enough to keep me guessing and stop my progress. I hope the following information will can help some of you succeed with your scrapers.

Lie-Nielsen offers two different sets of card scrapers, made out of high carbon Swedish Tool Steel, and hardened to Rockwell 49-51. These include a two-pack Hand Scraper Set and a four-pack Gooseneck Scraper Set. The scrapers in the two-pack Hand Scraper Set are both rectangular. One scraper is .032” thick and the other .020” thick. I like to choose the thinner scraper when I’m planning some super-light finesse type removal, even though I know I could still get the aggressiveness needed out of both. The scrapers in the four-pack Gooseneck Scraper Set are comprised of one large and one small, with one each in the same plate thicknesses of .032” and .020”, as the rectangular versions. The different sizes afford different curves and shapes, to cover even more woodworking territory.

Lie-Nielsen offers two different sets of card scrapers, made out of high carbon Swedish Tool Steel, and hardened to Rockwell 49-51. These include a two-pack Hand Scraper Set and a four-pack Gooseneck Scraper Set. The scrapers in the two-pack Hand Scraper Set are both rectangular. One scraper is .032” thick and the other .020” thick. I like to choose the thinner scraper when I’m planning some super-light finesse type removal, even though I know I could still get the aggressiveness needed out of both. The scrapers in the four-pack Gooseneck Scraper Set are comprised of one large and one small, with one each in the same plate thicknesses of .032” and .020”, as the rectangular versions. The different sizes afford different curves and shapes, to cover even more woodworking territory.

Before I proceed, let me answer the basic question: What is a scraper? I bet most people would likely imagine a card scraper. I know that was the case for me for a long time, although there are certainly other types. Ultimately, I define a scraper as a tool that removes material, in a manner other than via a knife type cutting action. Whether we are talking about a card scraper (rectangular or goose necked), a scraper plane, or anything else in the category, I’ll try to provide some useful tips and info.

One of the first things I do, when I get a scraper, is to spend time sharpening the tool. To lay some groundwork, both the narrow edges and face edges of a card scraper must both be honed to a high level. If either of these is overlooked or not worked to the same level, it will be the limiting factor of your final tool. Personally I work these surfaces up through my 8000 grit water stone, but some still hone to a higher grit. It is a great idea to have a 10X-magnifying loop, so you can SEE your work, rather than guessing a certain number of strokes automatically equals finished. Now, if it is the first sharpening, I expect to spend more time than on the subsequent trips to the sharpening bench. This may seem odd, but most new scrapers come with at least some mill marks, which you only need to remove the first time.

When I begin sharpening a rectangular card scraper, I first work the narrow edges with a fine file, which is a quick method to both verify a 90-degree juncture and that the narrow edge surface is without dips from end-to-end. The handle on this tool is what I call a thick oval, which helps me in the filing portion of this task. I clamp the scraper in my vise, so its height matches what is needed to keep the file flat and parallel, while the handle physically rides on the bench. This ultimately acts somewhat like a jig that can never get lost. With the fact that it is somewhat easy to negatively modify the scraper’s edge shape when using a file free handed, I think it wise to at least explore a jig at first. If you are using a file that is flat, you can cut a slot that is 90-degrees to the face into a piece of wood. Put the file into the slot, and then work the narrow edge against the file, while holding the face so it stays flush to the wood.

After removing any heavy mill marks with the file on both of the narrow edges, its time to move to the stones. When working the edges, I hold the scraper against a purpose-made 90-degree block of wood, on the water stone. This allows me to remove material while retaining the proper square orientation of the edge to the face. Just squeeze the scraper to the wood, and let both ride together over the stone. I push them straight up and down the stone, but with both wood and scraper rotated so they look like I would travel diagonally, so there is less chance of carving tracks into the stone. Check the progress until the scraper edge is a consistently flat matte grey. Depending on your setup, you can decide to move directly to a 8000 grit water stone, or if you have an intermediate like a 4000 grit, you can work through all three. Just let your eyes and loop guide when you’ve finished. After the 8000 grit stone, your narrow edge surface should look similar to a mirror, with no discolored areas.

The next step is to hone the faces of the scraper. From experience, this portion can go from good to bad in a heartbeat. What I mean is there is usually enthusiasm when first starting this phase, but that can turn into disgust quite rapidly when checking the progress. For those who have never sharpened the faces, you’ll usually see certain areas showing signs of your work, and others that will be completely devoid of contact, almost without regard for time spent. Part of this issue is related to unequal pressure along the face while honing. If you are just using finger pressure on the scraper plate, I’ve found no way to totally prevent the off/on contact points consistently. This is where David Charlesworth’s ruler trick, that I also employ when sharpening all of my plane irons, can play a role in the scraper sharpening. When using his trick in the sharpening of the backs of plane irons, it focuses the work out at the very edge, rather than spending time to polish the full back surface of the iron. Similarly, we can use it to focus on the face surface where it meets the previously polished narrow edges, since the edge/face combo is the only area that will interact with your wood. To make this work, the other component I use is a piece of 3/4” MDF that is about 2/3 as wide as my scraper. I try to have the MDF about the same length as the scraper, but it can be a little longer without causing problems. While the Charlesworth trick does an excellent job of focusing the honing work out towards an edge, the importance of the MDF in this application rises as the flexibility of the scraper increases. I used some thin double-sided carpet tape to apply the MDF flush to one narrow edge on my scraper. I place a thin ruler along the long edge of my 1000 grit water stone, which is held in place by water tension. To orient properly, the scraper portion left unexposed by the MDF will be on the opposite side of the stone from the ruler. This allows it to flex slightly and work from the edge in towards the centerline of the scraper. The movement is just front and back, as there are no thin edges to gouge the stone. It will produce a narrow surfaced area likely less than 1/8”, so don’t expect it to be very wide, and don’t worry if it is not. A consistent thin area is all that you need. Same as before, you can choose to work it on an intermediate stone, prior to the 8000 stone, or not. Let your results (and your loop) guide you.

Before moving to the next stage of preparation, I wanted to include some information that I hope users might both find interesting and useful, or at least expand their thoughts of scrapers. Recently, while building a very figured electric guitar, I had an area on the top where none of my scrapers “fit”, to resolve an issue. I recalled using a tool that many would think classified at the far end away from scrapers, once upon a time, that might just work. I picked up one of my recently sharpened bevel-edged chisels, that is about 3/16” wide. Without changing any sharpening aspect, nor apply a burr/hook, I stood the chisel upright, leaned it so the flat back was a bit towards the direction I meant to travel, and took a couple of light passes. It took some very controlled super light type shavings, and left a wonderful result. This obviously doesn’t work only with narrow chisels, but finding a tool that fits your needs is the main point. Beyond that, hopefully it points out that while there are times to use a burr/hook on a scraper, it is not always a necessity. Without the added burr/hook, a scraper is less aggressive, but this can be a good thing. If using a scraper to blend or finalize, I find it easier to remove exactly what I want. Another positive, and one I relish when using a scraper plane, is how I can set the cutting angle one time, and quickly have the same great results, without the need to dial in after each sharpening. If I added a burr/hook, there are much greater chances I’d spend extra time re-obtaining the sweet spot each time, but let your work dictate using a burr/hook or not. In the scope of a job, I find the setup operations are just part of woodworking. Keep your options open.

When applying a burr/hook to the prepared card scraper, make sure your burnishing tool is harder than the scraper. In the past this was much easier to accomplish, as many of the scrapers were pretty soft, but some of the newer scrapers are hardened to a higher degree, which while upping the ante for preparation, will help the edge last longer, too. Another important aspect relating to burnishers is their level of polish. The surface of the burnisher, where it contacts with the scraper, should have no scratches. I’m sure it’s easy to visualize that scratches on a hard tool will easily transfer over to the less hard tool. Before using my burnisher on a scraper, I like to apply a little Camellia or Jojoba oil to both. You can get by without, but the reduction in friction helps it work more smoothly. I start with the card scraper flat on my bench, with the narrow edge I’m working just inside the bench top edge so it doesn’t hang off. I take my burnisher and keeping it flat on the face edge of the scraper, move the burnisher from end to end, with just a small amount of pressure. After doing this for no more than 30 seconds, I’ll do the other three similar face edges. I look at this as minutely moving the metal towards the narrow edge of the scraper, setting up for the burr/hook.

One of the first times I was successful in creating a burr/hook, I handled the next step slightly different than I do now. That time, I’d placed the scraper into my tail vise at this point, to hold while I turned the burr/hook. I’d just installed a new light receptacle above the vise (totally coincidentally) and had the light on. I took my burnisher, and with it almost completely parallel to the narrow edge, ran it lightly over the scraper. My second pass is what caught my eye. I lowered the angle by a couple to maybe five degrees, and made a second light pass. With the light directly above the working area, I saw a very thin gleam grow across the scraper, behind the burnisher on that second pass. I felt the edge and the burr/hook was quite small, but consistent all the way across. I took the scraper out of the vise, so I could verify whether what I was seeing was truly usable feedback. It worked wonderfully, and lasted much longer than any I’d ever created before. I think this makes sense, as a longer burr/hook would seem to weaken quicker and easier, as length increases flexibility. Now that I knew the amount of pressure required to create the burr/hook was almost minimal, I regularly just hold the card scraper in my left hand, applying light pressure with the burnisher with my right, rather than placing it in a vise.

The goose neck scrapers have quite a bit of similarity to the rectangular card scrapers, but require a couple of different tools to handle similar issues. For the mill mark removal, some of the outside curved edges can still be worked with a straight file, but if you need to use the inside curved surfaces to work on small cylindrical pieces or similar, then I use a small round file. I try to make sure to use a file with either no taper in the section I’m using, or as little as possible. This helps keep the narrow edge at 90 degrees to the outside faces. Small cylindrical ceramic slips in different grits can allow this same section to get close to the results obtained on the rectangular scrapers, where you would use a water stone. When I’m ready to work the face edges of the gooseneck scrapers, I still utilize the Charlesworth trick, but I find it is a bit more piecemeal, due to the fact I’m working around a curve. Similarly, following up on the burr/hook requires more patience, and a smaller burnisher can be a necessity in certain areas. All in all, the gooseneck scrapers do require a bit more touch and finesse, but achievable results are within reach and are so very useful.

Scrapers will always have a place in my kit, as they can certainly save the day. Hopefully, you’ll give them a try and find they are a good addition to your present methods, providing some valuable options. Feel free to contact me at leelairdwoodworking@gmail.com if you have any questions, or if you have suggestions for future articles you would like to see.

To take a closer look at the Lie Nielsen scrapers, click here.

To see Highland Woodworking’s entire selection of Lie-Nielsen hand tools, click here.

To return to the August 2015 issue of Wood News Online, click here.

Lee Laird has enjoyed woodworking for over 25 years. He is retired from the U.S.P.S. and worked for Lie-Nielsen Toolworks as a show staff member, demonstrating tools and training customers. You can email him at LeeLairdWoodworking@gmail.com or follow him on Twitter at twitter.com/LLWW

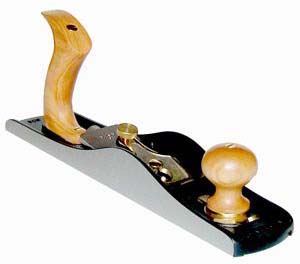

The first scraper plane is the model 212-Iron scraping plane, which is based on the Stanley No. 212. This is a small format scraper plane, and the Lie-Nielsen version has a plane body made of ductile cast iron. The blade is 1/8” thick A2 steel, which is thicker than the original Stanley irons, and helps minimize chatter. The iron’s adjuster, on this plane, allows the user to change the angle at which the iron sits in the plane, and dial in the sweet spot. I set my iron so it leans forward (away from the wooden handle) approximately 15 degrees, which seems to be the optimum angle. If the wood I’m working doesn’t cut well with the normal setting, I’ll carefully take the iron out of the body. I always remove the iron through the sole of the plane, to reduce chances of dinging the sharp iron. By holding the iron as if it were a card scraper, I can quickly find the angle where the wood cuts best. There are three options I’ve used to transfer the new angle to the plane. While holding the iron at the new angle, I can either: move the plane body up beside the iron and adjust the frog so it matches this angle; grab my protractor, so I know the angle that works with this wood; or instead, put a piece of light colored scrap wood against the edge of the iron, and draw a line I can again reference when I replace the iron in the body. To replace the iron in the body, I always come up through the sole of the plane body, again working towards saving my sharp edge. I choose the No. 212 when I’m working small flat pieces, like one might expect in boxes, picture frames or even small tables. There is nothing to prevent one from using the No. 212 on a larger flat surface, like a large table, but it would just take more passes with the smaller width of this iron. There is something about this sized scraper plane that just feels good in the hand, much like reaching for that favorite block plane.

The first scraper plane is the model 212-Iron scraping plane, which is based on the Stanley No. 212. This is a small format scraper plane, and the Lie-Nielsen version has a plane body made of ductile cast iron. The blade is 1/8” thick A2 steel, which is thicker than the original Stanley irons, and helps minimize chatter. The iron’s adjuster, on this plane, allows the user to change the angle at which the iron sits in the plane, and dial in the sweet spot. I set my iron so it leans forward (away from the wooden handle) approximately 15 degrees, which seems to be the optimum angle. If the wood I’m working doesn’t cut well with the normal setting, I’ll carefully take the iron out of the body. I always remove the iron through the sole of the plane, to reduce chances of dinging the sharp iron. By holding the iron as if it were a card scraper, I can quickly find the angle where the wood cuts best. There are three options I’ve used to transfer the new angle to the plane. While holding the iron at the new angle, I can either: move the plane body up beside the iron and adjust the frog so it matches this angle; grab my protractor, so I know the angle that works with this wood; or instead, put a piece of light colored scrap wood against the edge of the iron, and draw a line I can again reference when I replace the iron in the body. To replace the iron in the body, I always come up through the sole of the plane body, again working towards saving my sharp edge. I choose the No. 212 when I’m working small flat pieces, like one might expect in boxes, picture frames or even small tables. There is nothing to prevent one from using the No. 212 on a larger flat surface, like a large table, but it would just take more passes with the smaller width of this iron. There is something about this sized scraper plane that just feels good in the hand, much like reaching for that favorite block plane. The other scraper plane is the model 85, which again is based on an original Stanley model; The No. 85 Cabinet Maker’s Scraper. This plane body is also made of ductile cast iron, which strengthens the body, and will likely save the tool from the accidental fall to the floor. The iron again is 1/8” thick A2 steel, but it is shaped somewhat like an upside down “T”. There are some unique features in the No. 85. First, this plane has a full width iron, so it can work against an adjacent vertical surface. Another unique feature, which dovetails with the first, is the handle adjustability. Both the front and rear handles can rotate (after loosening) either left or right, to help prevent the user’s knuckles from contacting adjacent wood. The No. 85 does not have the angle adjuster for the iron, and with the iron’s angle hardwired, can be a bit easier to set up.

The other scraper plane is the model 85, which again is based on an original Stanley model; The No. 85 Cabinet Maker’s Scraper. This plane body is also made of ductile cast iron, which strengthens the body, and will likely save the tool from the accidental fall to the floor. The iron again is 1/8” thick A2 steel, but it is shaped somewhat like an upside down “T”. There are some unique features in the No. 85. First, this plane has a full width iron, so it can work against an adjacent vertical surface. Another unique feature, which dovetails with the first, is the handle adjustability. Both the front and rear handles can rotate (after loosening) either left or right, to help prevent the user’s knuckles from contacting adjacent wood. The No. 85 does not have the angle adjuster for the iron, and with the iron’s angle hardwired, can be a bit easier to set up.