The tree had been down for years. I have a hard time identifying trees, but I knew this was a cherry tree by the look of its bark. Scattered along this otherwise flawless limb were several unsightly growths—the burls I had been searching for.

Years earlier I had attempted to use my chainsaw but it wouldn’t start. I practically yanked my shoulder out of its socket trying to get it going, but no luck. What I wouldn’t find out until almost a year after this current cherry tree episode is that the typically fluorescent green fuel line in the chain saw went to a gummy brown, and then to about a dozen brown-black bits of hard plastic which in no way resembled a functioning gas line. All I knew at the time was that it did not work. I grabbed my bow saw.

This downed cherry tree was only about six inches at its widest diameter and I could see at least four burls in it of various sizes. I began cutting. A couple of minutes later, I took off my hat. A couple of minutes after that I took off my sweatshirt. A few minutes after that my arm fell off—and I wasn’t even through the first cut. I switched to my left arm, but this was proving useless, so I just rested a bit.

Alternating between resting, sawing, cussing, and contemplating just how out of shape I really was, I managed to get five logs cut—three with burls, and two straight grained. I moved the logs into my shed and painted the end grain with leftover latex paint—I have no idea where this pink paint came from, but it looked like the logs had polished “fingernails.” I then locked the shed and went in the house. I felt I earned a beer.

My intention was to let the wood dry out over a year or more, but curiosity wouldn’t allow that. A month after giving the logs pink fingernails I found myself cutting a bowl blank out of one of the cherry burls. I took a small piece of wood from the leftover scraps after cutting the bowl blank and sanded it smooth through a succession of finer grit sandpaper. I then dabbed a little linseed oil onto the scrap and rubbed it in with my thumb. I was amazed! This little scrap of wood—about four inches long by two inches wide and only a quarter of an inch thick—had incredibly beautiful grain! Only an inch of its length had straight grain, but then the burl kicked in with its many random swirls. It was visually stunning—and only a piece of scrap!

Like a faithful dog tail-waggingly bringing a well-moistened tennis ball back to its master, I ran into the house to show my wife. I held it up in front of her cradled gently in both hands as if I was Indiana Jones holding an ancient gold relic. I waited for her to share her excitement with me.

“That’s nice,” she said the same way she would describe a shirt I was wearing that she didn’t like.

I was stunned for the second time that day—I could hear my bubble burst. “That’s nice? That’s all?”

“It’s nice, yes.”

“This is cherry burl! I have three logs of it in the shed for bowls!”

“That doesn’t look like a bowl.”

“It’s not, this is just a scrap leftover from cutting a bowl blank.”

“That’s nice. Punch a hole through it, add some string, and you can wear it around your neck.”

Okay, she didn’t say that last bit, but that is what I heard. I realize that people view things differently, but where did I get this almost absurd love for something as simple as an interesting wood grain pattern? In an effort to find out, I proudly took my scrap of wood over to show my father. He took it from me and stared silently for a few moments before responding.

“Wow!” He said softly. “Look at this grain—this is beautiful!”

Okay, I thought to myself, this explains it; it must be genetics—this not only explains my reaction but also my wife’s. Then my father told me something that reinforced this and revealed a lot about our family and who I am.

“My father,” he began, “kept a piece of wood in his pocket that he thought was pretty. I don’t remember what kind of wood it was, but it was an oval piece, only about a quarter of an inch thick, and he told me he added several coats of linseed oil to it, each one rubbed in by hand. He got a kick out of showing people. I guess that’s where I get my appreciation for such things.”

And I guess that’s where I get my appreciation for such things. And I do remember my grandfather showing me that scrap of wood. I remember him taking it out of his pocket and reverently showing it to me as if it were a fine piece of heirloom furniture that not only had value but that I would likely someday inherit. I was very young at the time so I don’t remember my exact reaction, but I’m guessing I thought he was crazy—just like my wife thought I was crazy when I showed her my little piece of scrap! I suddenly not only knew exactly how she felt, I understood it. I don’t blame her for her reaction—this silly love of interesting wood grain patterns is in my blood, not hers.

I would later turn a bowl out of one of the larger pieces of burl from this downed cherry tree and give it to my father—I knew he would appreciate it.

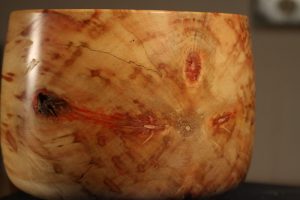

This shows the bottom of the natural edge cherry bowl where you can see six knots.

This shows the interior of the natural edge cherry bowl showing the interesting grain patterns caused by two of the larger knots.

And this is why I love turning bowls so much. The reason is simple—it is what you can’t see—what’s inside—that makes bowls special. I have made chairs and other small pieces of furniture, turned tool handles and carving mallets, and built the obligate birdhouses, but by far, my favorite woodworking hobby is bowl turning. You can use a board in construction of furniture and, even after finishing, you see the grain pretty much as it was before you started. But in bowls, you really can’t tell how the finished piece is going to look until after it is turned. I have “accidentally” discovered interesting insect damage in walnut, spalt in maple, half a dozen interesting knots in a busy crotch of cherry, and a glorious red stain in box elder. And with burls, the unknown is much greater—you really never know what the grain is going to look like or what inclusions figure the wood.

Close-up of box elder bowl showing detail of spalt and red coloration.

I truly love this “discovery of the unknown” aspect of bowl turning; anxiously excited to see what’s inside.

Return to the January 2017 issue of The Highland Woodturner